RAG1 and RAG2: Discovery, Mechanism, and Evolution of the V(D)J Recombinase

| Part I (you are reading this) | Part II | Part III |

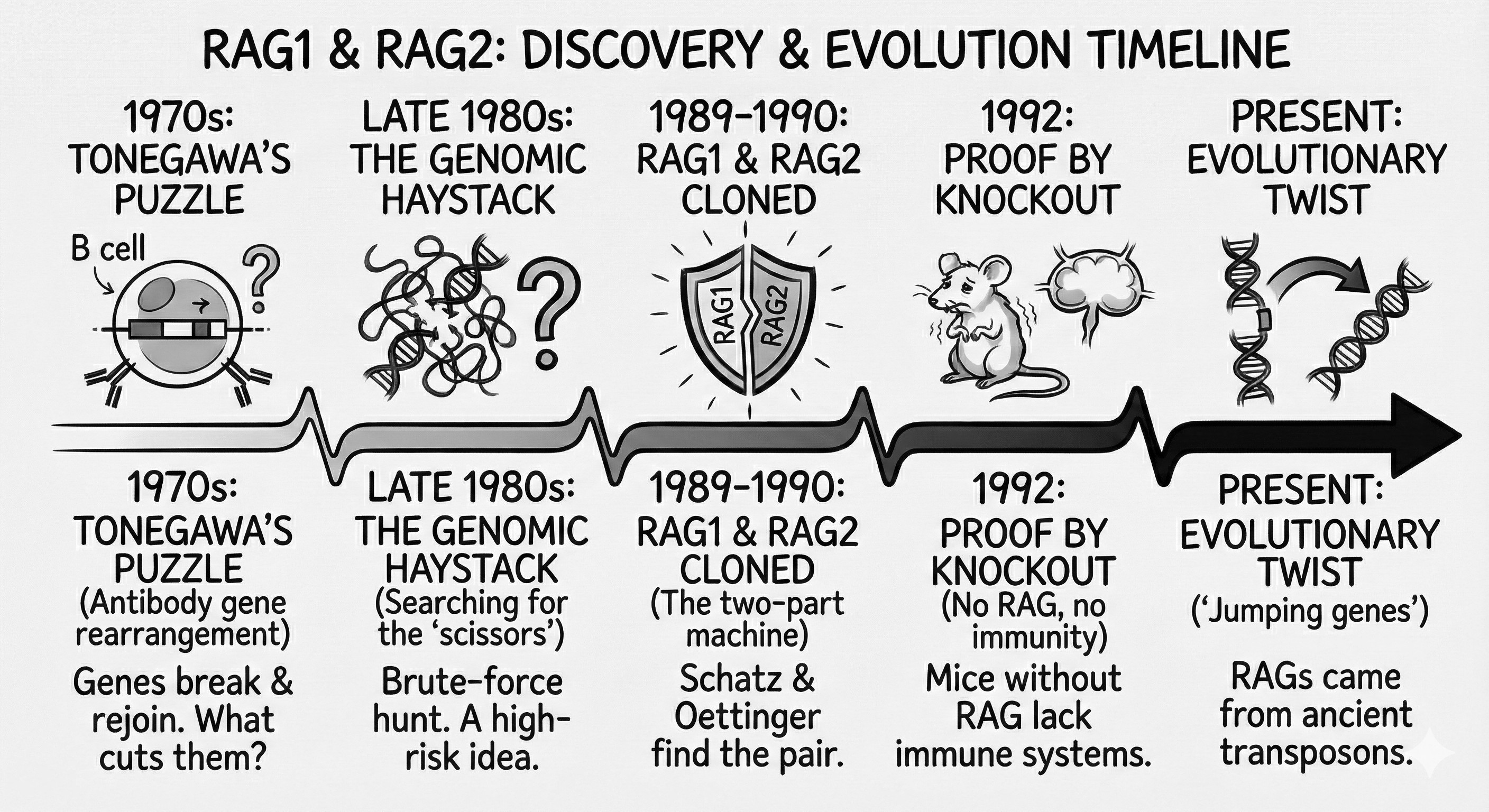

The adaptive immune system depends on a controlled act of genomic violence. To recognize an almost infinite variety of pathogens, developing lymphocytes deliberately break and rejoin their own DNA, assembling antigen receptor genes from modular fragments. For decades, immunologists understood the outcome of this process but not its cause: what enzyme could cut the genome so precisely, and why did it act only in immune cells?

The answer emerged at the end of the 1980s with the discovery of RAG1 and RAG2, two genes that together form the molecular “scissors” of V(D)J recombination. Their identification not only solved a long-standing mystery in immunology but also revealed that the origins of adaptive immunity lie in an ancient, repurposed genetic element. This account follows the scientific hunt for the RAG genes and the far-reaching consequences of their discovery.

The Hunt for the Immunological “Scissors” (1970s–1980s)

In the 1970s, Susumu Tonegawa (a Japanese molecular biologist trained in Tokyo and California) stunned the scientific world by showing that antibody genes rearrange in B cells, which was a finding that earned him the 1987 Nobel Prize. This process, now called V(D)J recombination, explained how a finite genome could produce the vast diversity of antibodies and T-cell receptors. Yet a mystery remained: what molecular “scissors” cut and rejoin DNA to make these receptor genes? Through the 1980s, immunologists imagined a dedicated V(D)J recombinase that was selectively expressed in lymphocytes was behind this phenomenon. The race was on to find it. Remarkably, Tonegawa did not participate in this race for too long as after securing his place in immunology history, he switched fields to neuroscience, applying his scientific boldness to memory and learning research.

By the late 1980s, one approach to find the elusive recombinase was brute-force genetics. Among those intrigued was David Baltimore, already famous for co-discovering reverse transcriptase (Nobel Prize, 1975) and now pivoting to immunology. Baltimore, at MIT’s Whitehead Institute, suspected that transferring the right gene into non-immune cells might confer the ability to perform V(D)J recombination. It was a high-risk idea—like finding a needle in a genomic haystack—but worth a shot.

Cloning RAG1 and RAG2: Breathing Life into Fibroblasts (1988–1990)

In 1988, Baltimore’s team (most notably graduate students David Schatz and Marjorie Oettinger) developed an ingenious assay. They engineered a reporter plasmid containing artificial gene segments and RSSs (Recombination Signal Sequences) that would produce a detectable signal only if V(D)J recombination occurred. This reporter was transfected into NIH-3T3 fibroblasts, cells normally incapable of gene rearrangement, along with immune-cell DNA.

Through serial genomic transfections, they isolated a genomic locus that conferred recombination activity. In late 1989, they identified a gene encoding a 1040–amino acid protein that activated V(D)J recombination in fibroblasts. They named it RAG1 (Recombination Activating Gene 1). RAG1 expression was restricted to lymphoid tissues—exactly where the scissors should be active.

This was a great accomplishment but a piece of the puzzle was still missing: RAG1 alone was not sufficient for maximal activity, potentially hinting at a missing partner that was yet to be discovered. 2 years after their discovery of RAG1, in June 1990, Oettinger and Schatz reported RAG2, a gene adjacent to RAG1 that synergizes with it to produce full recombination activity. Interestingly, RAG2 was lacking obvious enzymatic motifs but without RAG2, RAG1 was a dull knife. Only together, RAG1 and RAG2 reconstituted the V(D)J recombinase at expected levels.

The molecular scissors were a two-part machine. After these breakthough findings, then-graduate-students David Schatz and Marjorie Oettinger eventually became leaders thmselves and continued working on V(DJ) recombination and the RAG proteins. David Baltimore later reflected that identifying RAG proteins was among his lab’s proudest achievements.

Proof by Knockout: No RAG, No Immune System (1992)

Discovery in vitro was only the beginning. In 1992, two groups independently generated RAG knockout mice. Published back-to-back in Cell, the results were unequivocal.

Peter Mombaerts (of Tonewaga lab) showed that in RAG1-KO mice, there were no mature B or T lymphocytes; thymus and lymph nodes were severely underdeveloped; immunoglobulin and TCR genes remained unrearranged; and interestingly the mice phenotype resembled a known human disease (more on this later). In addition to these, with this knockout mouse, Mombaerts showed that despite low-level brain expression reports of RAG1, RAG1-KO mice were neurologically normal. Like his mentor, Mombaerts also switched to neurogenetics and eventually become a leader in olfactory system research.

In parallel, Yuko Shinkai (of Frederick Alt lab) showed that in RAG2-KO mice, early lymphoid progenitors were present; V(D)J recombination initiation was completely failing; there was no detectable rearranged antigen receptor genes; and reintroduction of RAG2 rescued recombination in cultured cells. Shinkai, later, followed RAG2’s link to histone modifications and built his careers around epigenetics by studying chromatin regulation.

Together, these two amazing knockouts and their characterization proved that RAG1 and RAG2 were absolutely required for adaptive immunity. The details of how this pair of proteins accomplished recombination followed later on.

RAG Mechanism and Evolution: Jumping Genes to Immune Genes

Biochemical studies in the mid-1990s revealed that: RAG1 contained the catalytic DDE motif, typical of transposases; RAG2 acted as an essential cofactor; and core RAG1/2 proteins alone could catalyze recombination in vitro. Then came the stunning discovery of RAG proteins’ ability to mediate DNA transposition under artificial conditions, which led to the transposon hypothesis that RAG genes originated from an ancient mobile genetic element. It wasn’t until 2016 that the discovery of ProtoRAG in amphioxus provided compelling evolutionary evidence to this claim.

Epilogue: Legacy of the RAG Story

The discovery of RAG1 and RAG2 resolved a decades-old mystery and reshaped immunology, genetics, evolution, and medicine. What began as a search for DNA scissors revealed the molecular basis of immune diversity, the evolutionary domestication of transposons, and the genetic roots of immunodeficiency and autoimmunity. We now know that severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) is a human disease that is caused by null RAG mutations. When these RAG mutations are hypomorphic, they then lead to Omenn syndrome where patients show very limited T cell development and autoimmune-like inflammation. In some cases, bone marrow transplantation from healthy donors can cure these conditions by restoring functional RAG genes.

From clever reporter assays to definitive knockout models, the RAG story exemplifies how bold ideas, technical rigor, and human curiosity converge to answer fundamental biological questions. It is very interesting that two unassuming genes changed how we understand the immune system and life’s capacity for innovation.

References

- Evidence of G.O.D.’s Miracle: Unearthing a RAG Transposon

- RAG1 and RAG2 in V(D)J Recombination and Transposition

- A Novel Quantitative Fluorescent Reporter Assay for RAG Targets and RAG Activity

- David Baltimore – Biographical

- The V(D)J Recombination Activating Gene, RAG-1

- Role of Recombination Signal Sequences in Formation of Coding and Signal Joints

- RAG-1–Deficient Mice Have No Mature B and T Lymphocytes

- RAG-2–Deficient Mice Lack Mature Lymphocytes Owing to Inability to Initiate V(D)J Rearrangement

- Peter Mombaerts – Rita Allen Foundation Profile

- Cellular Memory Laboratory – Yoichi Shinkai

- The RAG Proteins in V(D)J Recombination: More Than Just a Nuclease

| Part I (you are reading this) | Part II | Part III |