FAS: The Death Receptor That Keeps the Immune System in Balance

| Part I | Part II | Part III (you are reading this) |

If you have ever watched a crowd surge toward an emergency, sirens blaring and lights flashing, you have seen the good side of a fast response. But the real test of any system is not only how quickly it mobilizes. It is whether it can stand down once the crisis is over.

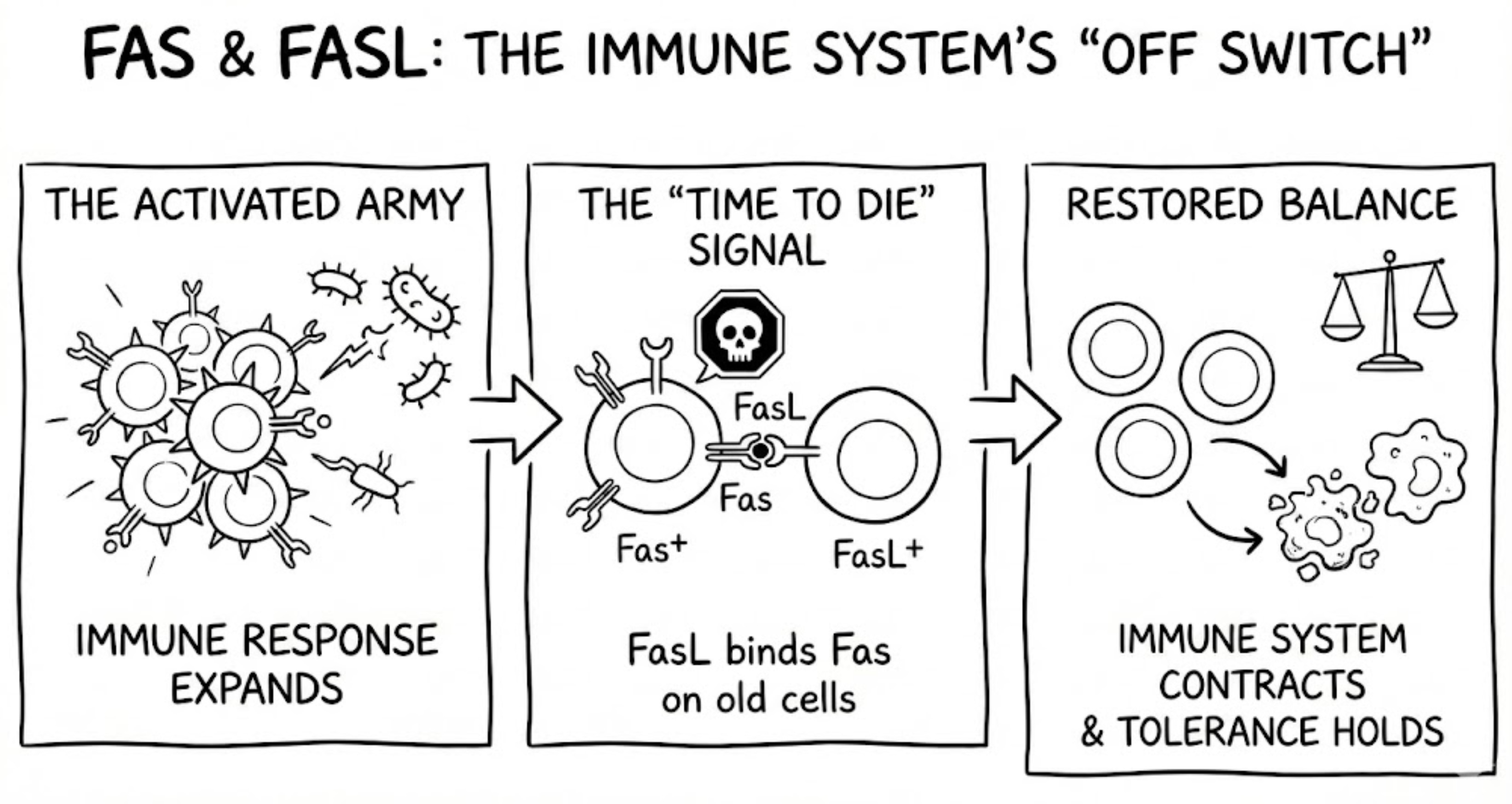

The immune system faces this exact challenge: it can expand armies of lymphocytes in days, but when the threat passes, those armies must shrink cleanly and quietly. FAS (also known as CD95 or APO-1) is one of the signals that makes this possible. When it works, immune responses resolve and self-tolerance holds. When it fails, immune cells linger like responders who never go home, filling lymph nodes, spilling into tissues, and sometimes turning their weapons inward.

This post focuses on peripheral tolerance, where the immune system actively deletes activated or autoreactive cells that escaped earlier checkpoints. Few pathways illustrate the necessity of timely disposal better than Fas, an accidental antibody finding that became a cornerstone of immunology, mouse genetics, and human disease.

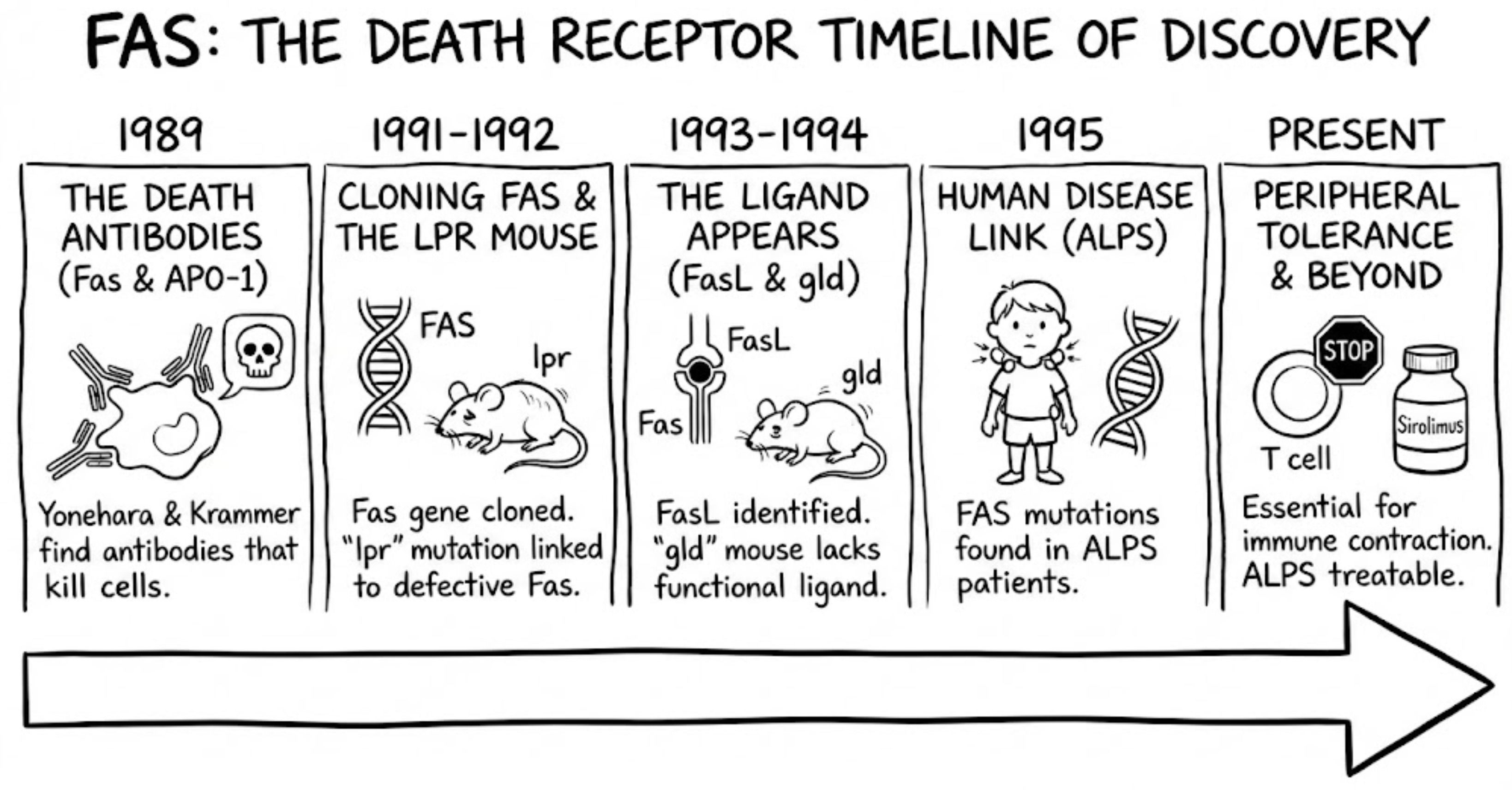

Two antibodies, two continents, one unsettling observation (1989)

In the late 1980s, monoclonal antibodies were already transforming biology. Most were used as labels or blockers: bind a protein, stop a ligand, map a marker. Then something unexpected happened in Tokyo.

Shin Yonehara and colleagues generated a monoclonal antibody, often referred to as CH-11, that did not merely bind a cell-surface protein. It killed the cell. Even more striking, the killing was enhanced when cells were sensitized with actinomycin D, a clue that what they were triggering was not nonspecific damage but a regulated program the cell could execute when survival transcripts were suppressed. In 1989, Yonehara reported this phenomenon and named the antigen “Fas” after the FS-7 cell line used during antibody generation, an oddly mundane origin for a receptor that would become synonymous with cellular suicide.

Almost simultaneously in Germany, Peter H. Krammer’s group, with Bernhard Trauth as first author, described an agonistic antibody against a surface molecule they called APO-1. Their antibody also triggered programmed cell death in tumor cells. The convergence was uncanny: two independent laboratories on different continents had found that binding a particular surface receptor could function as an off switch for cell survival.

At the time, discovering such antibodies was anything but straightforward. Researchers immunized mice with whole human cells, fused thousands of antibody-producing B cells into hybridomas, and then screened tens of thousands of clones by hand. Crucially, these screens were functional rather than descriptive: instead of asking whether an antibody bound a cell, they asked whether it did something dramatic, like halting growth or killing the cell outright. With no high-throughput assays, no genomics, and no rapid way to identify antibody targets, recognizing that a rare antibody was triggering a regulated death program rather than nonspecific toxicity required painstaking controls, intuition, and persistence. Confirming that the death was apoptosis relied on morphology, membrane blebbing, DNA fragmentation, and the absence of inflammation. Apoptosis is a tidy self-destruct mechanism. DNA is chopped into fragments, the membrane forms blebs, and the cell breaks into apoptotic bodies that can be cleared without triggering inflammatory chaos. In retrospect, the discovery of Fas and APO-1 looks inevitable, but at the time it was a low-probability find that depended as much on experimental courage as on technical skill.

By the end of 1989, the field was hooked. If Fas or APO-1 was a genuine death-inducing receptor, the questions were obvious: what was this receptor, why did immune cells carry it, and whatphysiological conditions triggered its expression?

From antigen to gene and the lpr mouse mystery (1991-1992)

Cloning Fas in the pre-genomic era (1991)

The next milestone required molecular cloning, and it reflected both the limits and ingenuity of early 1990s biology. In 1988, Yonehara approached Shigekazu Nagata, already known for work on cytokine receptors, to help isolate the gene encoding Fas. At the time, cloning meant building and screening cDNA libraries and validating candidates experimentally, not simply sequencing a sample and searching a database. The team had to build cDNA libraries from Fas-positive cells, express them in mammalian cells, and repeatedly enrich for the rare transfectants that gained anti-Fas antibody staining by flow cytometry. Early library screens even failed, forcing a switch to stronger mammalian expression systems.

In 1991, Naoto Itoh, Yonehara, Nagata, and colleagues finally cloned the human Fas cDNA and showed that Fas belongs to the TNF receptor superfamily. The protein carried a cysteine-rich extracellular domain and a cytoplasmic death domain. When expressed in cultured cells, Fas could mediate apoptosis: cells transfected with Fas would self-destruct when exposed to agonistic anti-Fas antibody. This turned a strange antibody effect into a new category of signaling molecule, the death receptor.

lpr mice were not hyperactive, they were failing to die (1992)

At the same time, immunologists had long been puzzled by a spontaneous mutant mouse strain called lpr, short for lymphoproliferation. Especially on autoimmune-prone backgrounds such as MRL, lpr mice developed massive lymph node and spleen enlargement, produced autoantibodies reminiscent of lupus, and suffered immune-complex kidney disease. Their lymph nodes filled with abnormal CD4-negative, CD8-negative double-negative T cells, an unusual population that became one of the most recognizable clues in immune tolerance genetics.

Mapping a mouse mutation in that era was slow and laborious. There was no whole-genome sequencing and no easy way to recreate candidate mutations to test causality. Geneticists had narrowed lpr to mouse chromosome 19, but the responsible gene remained unknown. Nagata’s newly cloned Fas gene offered a compelling candidate. In 1992, Rie Watanabe-Fukunaga in Nagata’s lab, working with NIH mouse geneticists Nancy Jenkins and Neal Copeland, examined Fas expression in lpr mice. The result was decisive: lpr mice showed almost no functional Fas expression, and a genetic lesion in the Fas gene explained the phenotype. Later work revealed different lpr alleles, including a retrotransposon insertion that disrupted transcription and a point mutation in the death domain, known as the lpr^cg allele, that rendered Fas nonfunctional.

This finding forged a direct link between defective apoptosis and autoimmunity. If activated T cells cannot receive the Fas time-to-die signal, they persist longer than they should, accumulate in lymphoid organs, and increase the likelihood of autoreactivity and tissue damage. The 1992 Nature paper went further, noting that Fas is normally expressed in the thymus and likely plays an important role in deleting autoreactive T cells, bridging central and peripheral tolerance.

How Fas kills: death by design

Mechanistically, Fas signaling turned out to be both simple and ruthless. When Fas is engaged by ligand or agonistic antibody, it trimerizes and assembles the death-inducing signaling complex, or DISC. The cytoplasmic death domain recruits the adaptor protein FADD, which in turn recruits procaspase-8, historically also called FLICE. Procaspase-8 molecules activate one another by proximity, then trigger downstream executioner caspases such as caspase-3. DNA fragments, cellular scaffolding collapses, and the cell is dismantled from within, usually without inflammation.

By the early 1990s, the picture was coming together: a TNF-family receptor on lymphocytes that could trigger apoptosis, a mutant mouse lacking this receptor that developed autoimmune lymphoproliferation, and a mechanistic pathway linking receptor engagement to caspase activation. One crucial piece was still missing: the physiological ligand.

Fas ligand and the gld mirror image (1993-1994)

The ligand appears (1993)

Every receptor needs a ligand. For Fas, the search concluded in late 1993 when Nagata’s group identified and cloned Fas Ligand, another TNF-family molecule expressed on activated T cells and natural killer cells. This discovery made Fas biologically intuitive. Cytotoxic lymphocytes could eliminate targets by engaging Fas, and immune responses could terminate through activation-induced cell death, a contraction phase that prevents chronic immune activation and preserves self-tolerance.

gld mice complete the genetic picture (1994)

At nearly the same time, attention returned to another autoimmune mouse strain: gld, for generalized lymphoproliferative disease. gld mice developed a phenotype almost indistinguishable from lpr mice, yet the mutation mapped elsewhere. In 1994, researchers showed that gld mice carry a point mutation in the Fas ligand gene, producing a nonfunctional ligand unable to trigger Fas-mediated death.

The symmetry was striking. lpr mice lacked a functional Fas receptor. gld mice lacked a functional Fas ligand. Different mutations, same outcome: immune cells that should die persisted, lymphoid organs enlarged, and autoimmunity followed. Together, these mutants established the Fas and FasL pair as indispensable for immune regulation and tolerance.

A human syndrome finds its molecular cause (1967-1995)

Long before Fas was known, clinicians had described a rare childhood disorder characterized by chronic, non-malignant lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and autoimmune cytopenias, without infection or cancer. Frank Canale and Robert Smith first reported it in 1967. For decades, it remained a medical curiosity.

By the mid-1990s, immunologists had the tools and conceptual framework to connect this syndrome to the Fas pathway. In 1995, Frédéric Rieux-Laucat and Alain Fischer in Paris identified mutations in the FAS gene in children with Canale-Smith syndrome. That same year, an NIH team led by Jennifer Puck, Steven Straus, and Michael Lenardo independently identified FAS mutations in American patients with similar clinical features. The disorder was renamed Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome, or ALPS. A key genetic insight was that many cases involve dominant-negative FAS mutations. A single mutated allele can sabotage Fas signaling even when the other allele is normal, explaining autosomal dominant inheritance in many families.

Clinically, ALPS often presents early in childhood with persistent enlarged lymph nodes and spleen, along with autoimmune destruction of blood cells such as hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia. A striking laboratory hallmark is the expansion of CD3-positive double-negative T cells, sometimes comprising 15 to 30 percent of circulating T cells. These cells mirror the abnormal population seen in lpr mice and have become a diagnostic signature of the disease.

ALPS also highlighted a deep connection between apoptosis and cancer risk. When lymphocytes that should die persist, they not only drive autoimmunity but also increase the chance of malignant transformation. Patients with ALPS have an elevated risk of lymphoma. The connection works in the opposite direction as well: many tumors evade immune attack by downregulating Fas or exploiting FasL to eliminate infiltrating T cells.

Epilogue: From accidental discovery to modern immunology (1996-Present)

The Fas story is a textbook example of biology progressing from accident to mechanism to medicine. In 1989, antibody-induced cell death looked like a laboratory oddity. In the early 1990s, Fas and FasL became molecular entities with defined domains, defined signaling partners, and defined genetics, validated by two classic mouse mutants. By 1995, the same pathway explained a rare human disease, transforming a clinical curiosity into a diagnosable genetic syndrome.

Since then, the picture has only grown more nuanced: we now know that Fas signaling is not always a one-way route to apoptosis. Depending on cellular context and downstream pathway integrity, CD95 can also engage non-apoptotic signaling, including inflammatory or survival pathways. This complexity helps explain why directly activating Fas has proven risky as a therapeutic strategy, since some tissues, particularly the liver, are exquisitely sensitive to death-receptor signaling.

Immune tolerance is not a single mechanism but a layered system. When one layer fails, the result can be immunological chaos. Imagine a self-reactive clonotype that somehow slips through thymic negative selection, which happens from time to time because AIRE dramatically expands the self-antigen “training set,” but the thymus is not an omniscient filter, and some potentially problematic T cells still graduate from thymus. That is where Fas starts to matter most: once a T cell is repeatedly stimulated, especially in a chronic setting like persistent self-antigen exposure (leading to autoimmunity), the immune system can invoke a built-in off switch called activation-induced cell death. In effect, Fas helps ensure that a self-reactive T cell that “passed the exam” but misbehaves later does not get to stick around indefinitely.

So, in the case of self-reactive T cells and an immune system that cannot stop responding, Fas has taught immunology one of its most counterintuitive truths: controlled cell death is essential for a proper immune system.

References

- Yonehara S. et al., 1989 – First identification of Fas antigen via a cell-killing monoclonal antibody

- Trauth B. et al., 1989 – Monoclonal antibody-mediated tumor regression by induction of apoptosis (APO-1) (Science)

- Itoh N., Nagata S. et al., 1991 – The polypeptide encoded by the cDNA for Fas can mediate apoptosis (Cell)

- Watanabe-Fukunaga R. et al., 1992 – Lymphoproliferation disorder in mice explained by defects in Fas antigen (Nature)

- Takahashi T., Nagata S. et al., 1994 – Generalized lymphoproliferative disease caused by Fas ligand point mutation (gld)

- Rieux-Laucat F., Fischer A. et al., 1995 – Mutations in Fas associated with human lymphoproliferative syndrome and autoimmunity (Science)

- Ramaswamy M. & Siegel R., 2012 – “Twenty Years in the Fas Lane” review (J. Immunol.)

- ICCS Newsletter, 2011 – Overview of ALPS clinical features and Fas pathway defects

- Atlas of Genetics (Pierre Bobé, 2002) – The Fas–FasL apoptotic pathway and DISC formation

- Hu et al., 2025 – Fas mediates apoptosis, inflammation, and host defense

- FDA label – Rapamune (sirolimus)

- NIAID – Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome (ALPS) Treatment

| Part I | Part II | Part III (you are reading this) |